As a teenager in the late 1990s, Roi Awng remembers seeing tigers and other wild animals on mountains covered by deep green forest around her village in the Hpakant region, one of the northernmost parts of Myanmar.

But the tigers and wild animals have fled.

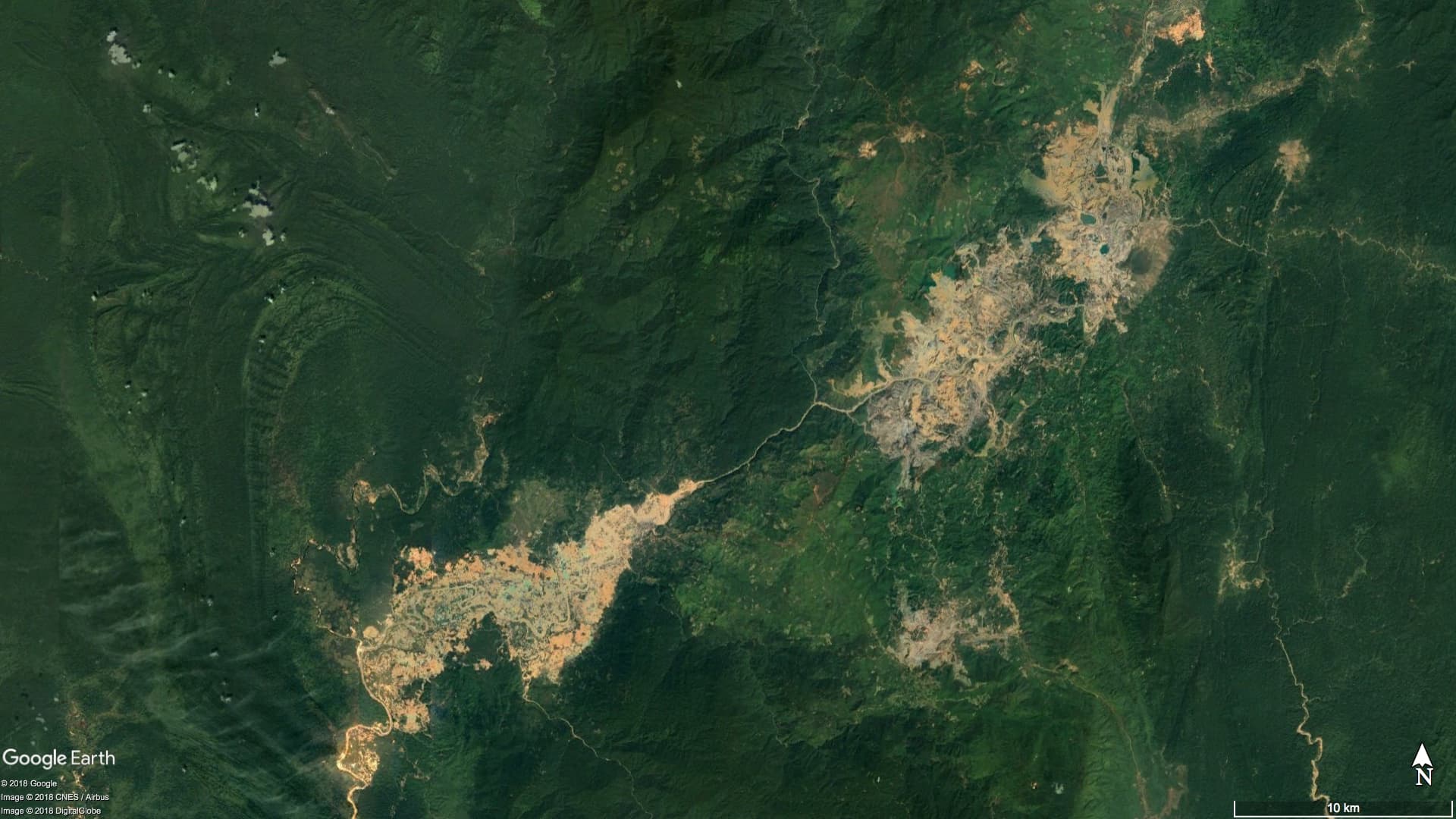

Two decades later, the landscape has undergone a vivid transformation. The forest is now a barren landscape, scarred by deep mining pits. The 32-year-old Kachin woman says many bright yellow trucks traverse the terrain and wheel loaders scoop out earth in a daily search for jade. Mining waste is improperly disposed of or towers in mounds hundreds of feet high. Sources of water and fisheries in Hpakant, the jade-rich area where her village is located, are polluted. Outside town, mountains are torn apart. Open pits are fenced with galvanized iron sheets.

Hpakant, an isolated area four hours by winding road from Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin, produces the world's highest quality jade, worth billions of dollars annually. Jade exploration and mining changes its ground-level visual reality every week. The local motorcycle driver I used on my visit is intimately familiar with the area. Nonetheless, he got lost multiple times amid the deep mining pits.

The region is also the epicenter of a convoluted, decades-long conflict between Myanmar's military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), one of the most powerful ethnic armed groups in the country. The armed forces and the KIA profit from concession fees and informal taxes imposed on mining companies.

In 1994, the KIA signed a ceasefire agreement with the then-ruling military junta, halting the ongoing conflict and opening up the region to mineral extraction. Larger-scale mining coincided with the resumption of armed clashes between the military and the KIA in 2011. During this conflict, the KIA lost much of its influence as the military gained more ground, leading to increased government control over mining licensing. The government bars foreigners from traveling to Hpakant, curtailing external scrutiny.

The leftovers from the take of the companies, the military and the KIA are divided between locals, itinerant informal miners and hand-pickers who migrate to Hpakant from different impoverished regions across the country, mainly Rakhine state. Census data for 2014 suggests that Hpakant had a total of 312,278 inhabitants. While the actual population might have changed from that figure due to constant flux in the region, local lawmakers and activists estimate nearly 300,000 of Hpakant’s residents are migrant miners, working either legally or illegally. They also said very little benefit from the jade trade eventually trickles down to local communities.

The actual size of Myanmar's jade industry is hard to estimate and research by various organizations present a wide range of figures. Whatever the precise figure is, the environmental and social costs are tangible, stark and visually obvious.

The following images show geographical changes in Hpakant over 34 years from 1984 to 2018, mainly due to jade mining. It makes use of satellite images and might take a few minutes to load properly.